The recent outpouring of anger about systemic racism triggered by police brutality requires us to ask, could we be unknowingly contributing to that problem? Could we be part of the system of institutional racism by the small act of tossing something in the trash?

“Environmental justice” communities–those that bear a disproportionate share of negative environmental consequences–bear the brunt of hosting hazardous waste facilities. Numerous studies have confirmed that race is the greatest predictor of likelihood of living near a hazardous waste facility in the US. Seventy-nine percent of all incinerators in the US are located in communities of color and low-income neighborhoods.

No one wants an incinerator or landfill for a neighbor. But corporate decision makers, regulatory agencies and local planning and zoning boards found it easier to site such facilities in low-income communities of color. Residents in these communities are less likely to have ties to decision makers on zoning boards or city councils who can protect their interests. Hiring technical and legal expertise is expensive. And in Latino communities, information in English-only documents is out of reach for affected residents who speak only Spanish.

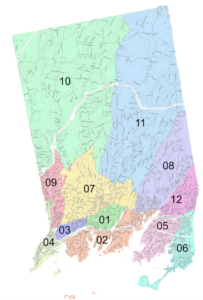

Incinerators contribute to air pollution, health risks, foul odors, community stigma and lower property values. Connecticut is no exception. CT’s main incinerator, the Materials Innovation Recycling Authority (MIRA), which handles 1/3 of CT’s waste, is located in Hartford, a city that is 80% Black and Latino. In addition to the lead, mercury, and dioxin emitted by MIRA, residents have to breathe the fumes of hundreds of diesel trucks delivering waste from 50 wealthier, whiter municipalities daily. MIRA was rated among the “dirty dozen” for its high emissions of carbon monoxide. 41 percent of Hartford children were found to suffer from asthma.

Incinerators contribute to air pollution, health risks, foul odors, community stigma and lower property values. Connecticut is no exception. CT’s main incinerator, the Materials Innovation Recycling Authority (MIRA), which handles 1/3 of CT’s waste, is located in Hartford, a city that is 80% Black and Latino. In addition to the lead, mercury, and dioxin emitted by MIRA, residents have to breathe the fumes of hundreds of diesel trucks delivering waste from 50 wealthier, whiter municipalities daily. MIRA was rated among the “dirty dozen” for its high emissions of carbon monoxide. 41 percent of Hartford children were found to suffer from asthma.

Both MIRA and CT’s last remaining landfill for incinerator ash are expected to close by 2024. The closing of MIRA and the Putnam landfill are part of a larger national trend. The life expectancy of an incinerator is 30 years. In the US the average incinerator is 31 years old. The industry saw at least 31 incinerators close since 2000, and there are only 73 incinerators remaining in the United States.

The closure of these facilities will drive prices up, as we compete with other municipalities and states for access to a shrinking resource. We may have to start trucking trash to Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and New York. Not only is this expensive, but putting thousands of diesel trucks on the road for such long hauls further exacerbates greenhouse gas emissions.

Incinerators and landfills not only impact communities of color–they impact all of us. Landfills are the third-largest human-generated source of methane emissions in the United States, a powerful greenhouse gas. Incinerators produce carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide–greenhouse gases–as well as hazardous particulate pollutants that damage human and wildlife health.

What can we as individual Greenwich residents do?

The most important thing is to be mindful about what we buy and what we throw out. Switching from single use to multi-use items such as reusable bags and straws, cloth napkins and kitchen towels instead of paper ones, are just a few ideas. You can find many more at https://www.wastefreegreenwich.org./

The most important thing is to be mindful about what we buy and what we throw out. Switching from single use to multi-use items such as reusable bags and straws, cloth napkins and kitchen towels instead of paper ones, are just a few ideas. You can find many more at https://www.wastefreegreenwich.org./

Secondly, get involved. The First Selectman will be forming an advisory group to study ideas for managing waste disposal in Greenwich. There are proven systems for metering trash that create incentives for reducing waste, by charging customers for only the amount they produce. You can find out more about this advisory group by contacting the First Selectman’s office at 203-622-7710.

The first step in overcoming systemic racism is recognizing our share in it. Let’s start by paying attention to the life of our trash after it leaves our homes. After all, there is no “away.”

Contact your selectman and make your voice heard.

If you’re inspired to take action, write to your RTM members and let them know how you feel.

Got Something to Say?